水疱性口炎病毒(VSV)是一种非致病性、有包膜的负链RNA弹状病毒,主要感染啮齿类动物、牛、猪和马等[1],在人群中的流行率极低,仅有个别动物饲养员和实验室人员的感染案例。感染后症状轻微或无症状。

VSV可以感染几乎所有类型的细胞,但由于I型干扰素(Interferons,IFN)介导的抗病毒反应,无法在健康细胞中引发生产性感染。然而,IFN信号缺陷通常与肿瘤发生同时发生[2-3]。因此,VSV能够感染并选择性地破坏癌细胞,而对正常细胞的损伤最小,同时,普通人群的抗VSV免疫较低这些特性使其成为理想的溶瘤病毒治疗剂[4]。

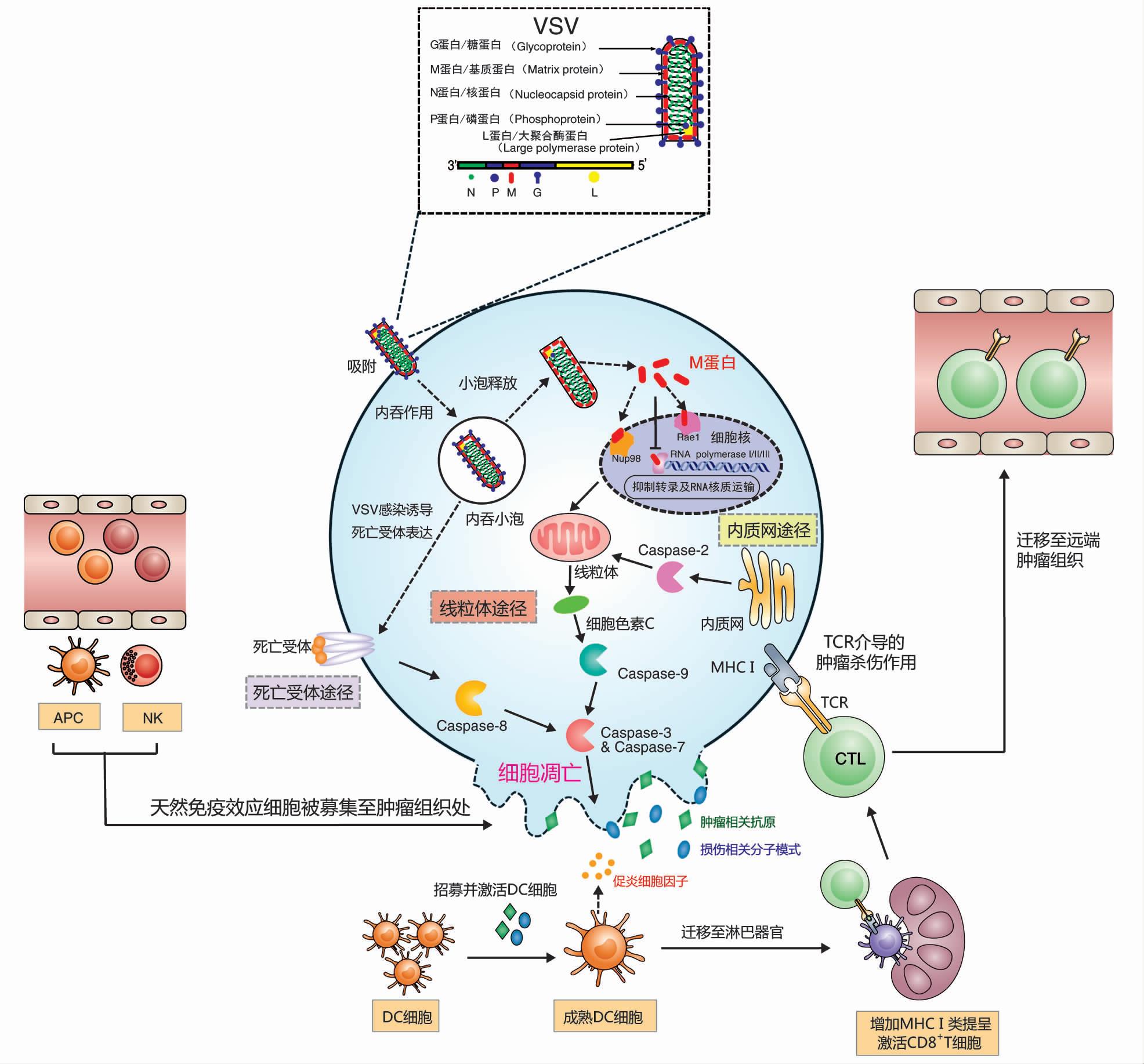

VSV基因组全长11161nt,从3'端到5'端依次编码5个蛋白:核衣壳蛋白(Nucleocapsid Protein,N)、磷蛋白(Phosphor Protein,P)、基质蛋白(Matrix Protein,M)、糖蛋白(Glycol Protein,G)及大聚合酶蛋白(Large Polymerase Protein,L)[5]。其包膜上的G蛋白通过与多种广泛存在于细胞膜表面的分子结合,启动病毒的感染过程[6]。M蛋白被证明可以抑制先天抗病毒反应并改变宿主转录机制,最终迫使肿瘤细胞发生凋亡[7]。VSV广泛的细胞趋向性是基于G蛋白,为提高VSV的溶瘤载体的安全性和选择性,通常用其他病毒的膜蛋白取代[8]。

图1:VSV的结构及其诱导的抗肿瘤机制(DOI:10.13523/i.cb.2001014)

2000年,Stojdl等[9]首次证实了VSV作为溶瘤病毒的潜力,他们发现在裸鼠上VSV能够明显抑制黑色素瘤的生长,而对正常组织细胞的影响很小。随后在多种肿瘤模型中也同样证实了VSV的溶瘤特性[10]。VSV作为溶瘤病毒拥有诸多优势:

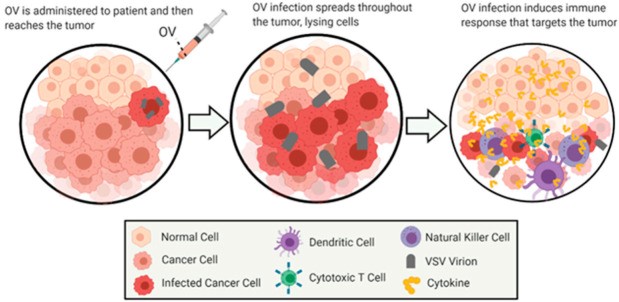

图2:溶瘤病毒疗法的一般概述。该图展示了使用VSV作为溶瘤病毒通过溶瘤病毒疗法治疗癌症的一般作用方法。这些图像描绘了恶性细胞随时间的感染和溶瘤作用,随后是侵入清除区域的细胞的免疫刺激。

尽管VSV在肿瘤治疗中拥有诸多优点,但野生型VSV仍然存在很多缺陷,这也是要对其进一步改造优化的原因。首先是安全性问题,主要表现为VSV潜在的神经毒性,已有大量研究证实了在啮齿动物模型中VSV颅内给药[12]、鼻腔给药[13]、血管内给药[14]以及腹腔给药[15]所导致的神经病变,而且在灵长类动物的丘脑给药中也观察到了严重的神经毒性[16];其次是病毒在机体存留时间较短影响溶瘤效果。在溶瘤治疗时往往需要进行多次给药,但VSV-G蛋白极易引起机体产生适应性免疫,重复给药时机体内存在的大量针对VSV的中和抗体会导致VSV迅速被清除而达不到理想的治疗效果,所以现阶段的研究都致力于提高rVSV的抗肿瘤活性及其安全性。

VSV关键蛋白基因的改造野生型VSV的神经毒性主要与其M蛋白的细胞杀伤作用和G蛋白的嗜神经性相关,对这两个蛋白基因的改造,是降低VSV神经毒性的主要方向。研究表明,将VSV-M蛋白上第51个氨基酸甲硫氨酸删除(VSVrM51)或将其替换成精氨酸(rM51R-M),能够解除M蛋白对感染细胞干扰素表达的抑制作用,从而提高病毒在正常组织细胞中的安全性[17-18]。

Janelle等[19]研究发现VSV的G蛋白突变病毒株(G5、G5R、G6和G6R),可以达到M蛋白突变(rM51R-M)类似的效果,即干扰素表达上升,神经毒性明显减弱;Roberts等[20]通过对G蛋白进行从第29个氨基酸到第9个氨基酸(CT9)或第1个氨基酸(CT1)的截短降低了VSV在神经系统中的复制能力;Duntsch等[21]的研究中利用删除了G蛋白基因的重组VSV载体(rVSV-rG)在瞬时表达VSV-G的细胞中包装获得单周期复制的病毒颗粒,体外实验证明其对正常神经元毒副作用极小,且对神经胶质瘤的杀伤作用不亚于野生型VSV。

溶瘤病毒在感染肿瘤细胞并对其杀伤的过程中,同时也会引起机体对病毒本身的免疫反应,机体内的循环抗体、非特异性宿主蛋白或补体蛋白中和病毒颗粒,会导致其被快速清除,最终影响溶瘤治疗效果。

目前有很多策略,首先是利用细胞载体递送、适体技术、PEG共价修饰等方式,使VSV在到达肿瘤部位前被暂时隔离,从而减少血液循环中VSV与中和抗体的接触以及被非特异性宿主蛋白或补体蛋白等中和,避免病毒被免疫系统过早清除。Tesfay等[22]通过被动免疫VSV中和抗体的方式证实了VSV的PEG化有效延长病毒在小鼠体内半衰期。第二种策略是通过调节体内免疫微环境,使其更利于VSV的复制。Muik等[23]利用嵌合病毒的方式,将不易诱导中和抗体产生的LCMV-G取代VSV-G,形成的嵌合病毒能够有效减少中和抗体的产生;Altomonte等[24]制备的VSV重组病毒VSV-gG能够分泌一种广谱的趋化因子结合蛋白——1型马疱疹病毒糖蛋白(gGEHV-1),在大鼠肝细胞癌模型中证实gGEHV-1的引入能够显著减少肿瘤微环境中的NK细胞和NKT细胞,大大提高肿瘤内病毒滴度从而提高治疗效果;同样,Wu等[25]证明表达鼠γ疱疹病毒68趋化因子结合蛋白M3的重组病毒VSV(MΔ51)-M3用于治疗大鼠多灶性肝细胞癌可减少病灶中NK细胞和中性粒细胞的积累,从而提高肿瘤中的病毒滴度和溶瘤效果。

增强VSV对肿瘤组织的直接杀伤作用,目前证实有效的方法包括整合抑癌基因、自杀基因、增强VSV对肿瘤组织的浸润效果以及联合其他治疗手段等。

除了增强对肿瘤的直接杀伤作用,VSV诱导更强的肿瘤特异性免疫反应对于肿瘤的彻底治愈也至关重要。

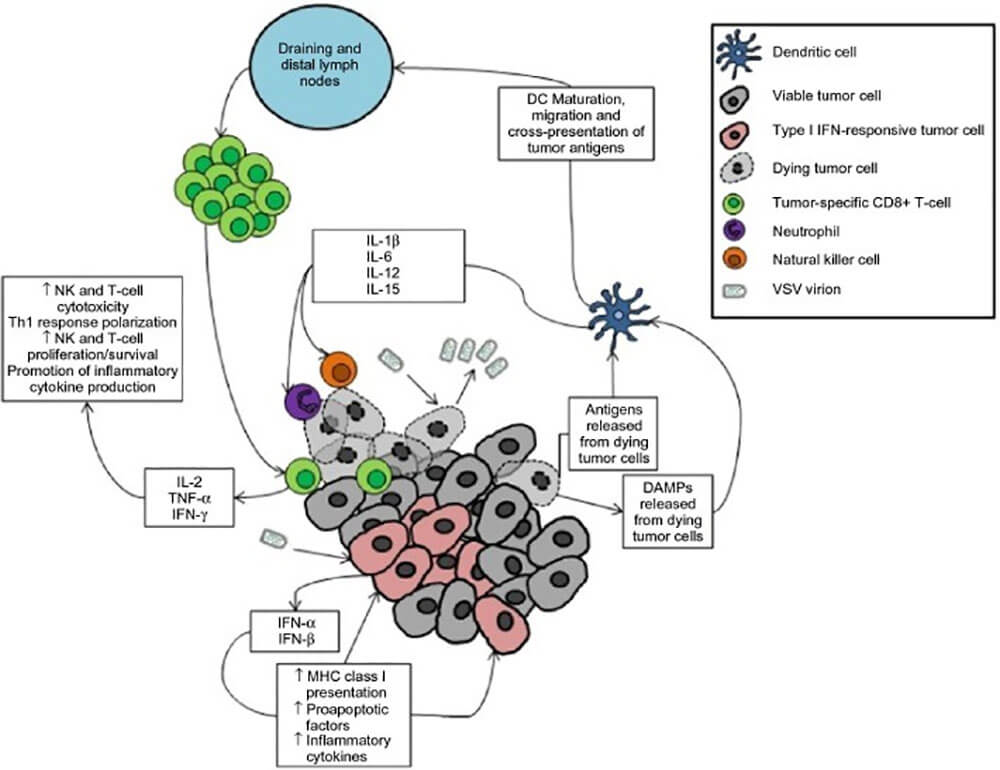

图3:由于转化细胞的病毒感染,VSV溶瘤病毒疗法可以产生抗肿瘤免疫(doi: 10.2147/OV.S66079)

注意:肿瘤减瘤是通过直接和间接的方式实现的。肿瘤细胞中的病毒复制将导致细胞病变效应并最终导致受感染细胞的死亡。同样,受感染细胞的先天抗病毒反应将通过I型干扰素信号传导的下游效应导致肿瘤细胞死亡。这与肿瘤抗原和危险相关分子模式(DAMP)的释放相结合,刺激了局部树突状细胞的成熟。成熟的树突状细胞分泌促炎细胞因子以募集先天效应细胞以介导肿瘤杀伤,并且它们迁移至肿瘤引流和远端淋巴结以将肿瘤抗原呈递给肿瘤反应性CD8+T细胞。活化的T细胞迁移到肿瘤并介导对肿瘤细胞的抗原特异性攻击。

近年来,随着VSV溶瘤病毒平台的持续发展,不断涌现出许多基于VSV改造的溶瘤病毒重组变体,主要针对提高肿瘤靶向性、延长体内存留时间、增强溶瘤效果等几方面,提升了VSV溶瘤病毒用于肿瘤治疗的安全性和有效性,一系列基于VSV的溶瘤病毒制剂也逐步进入临床试验阶段。

VSV在溶瘤病毒领域取得了一定成果,且具有非常广阔的应用前景,VSV作为治疗平台也表现的多种优势,例如高免疫原性、转基因相对容易插入其基因组、易于管理、广泛的趋向性等,但要实现肿瘤的治愈乃至预防复发,还需探寻更有效的治疗策略。因此,除了通过改造获得治疗效果更佳的重组VSV毒株,探索重组VSV溶瘤病毒与免疫检查点抑制剂、靶向治疗药物等其它治疗手段的联合也是具有发展潜力的研究方法。

参考文献

1. Drolet BS, Stuart MA, Derner JD. Infection of Melanoplus sanguinipes grasshoppers following ingestion of rangeland plant species harboring vesicular stomatitis virus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(10):3029-3033. doi:10.1128/AEM.02368-08

2. Ayala-Breton C, Barber GN, Russell SJ, Peng KW. Retargeting Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Using Measles Virus Envelope Glycoproteins. Human Gene Therapy. 2012;23(5):484-491. doi:10.1089/hum.2011.146

3. Jebar AH, Vile RG, Melcher AA, Griffin S, Selby PJ, Errington-Mais F. Progress in clinical oncolytic virus-based therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of General Virology. 2015;96(7):1533-1550. doi:10.1099/vir.0.000098

4. Barber GN. VSV-tumor selective replication and protein translation. Oncogene. 2005;24(52):7710-7719. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209042

5. Banerjee AK. The transcription complex of vesicular stomatitis virus. Cell. 1987;48(3):363-364. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90184-x

6. Johannsdottir HK, Mancini R, Kartenbeck J, Amato L, Helenius A. Host Cell Factors and Functions Involved in Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Entry. Journal of Virology. 2009;83(1):440-453. doi:10.1128/jvi.01864-08

7. Ahmed M, McKenzie MO, Puckett S, Hojnacki M, Poliquin L, Lyles DS. Ability of the matrix protein of vesicular stomatitis virus to suppress beta interferon gene expression is genetically correlated with the inhibition of host RNA and protein synthesis. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(8):4646-4657. doi:10.1128/jvi.77.8.4646-4657.2003

8. Hastie E, Cataldi M, Marriott I, Grdzelishvili VZ. Understanding and altering cell tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus. Virus research. 2013;176(0). doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2013.06.003

9. Stojdl DF, Lichty B, Knowles S, et al. Exploiting tumor-specific defects in the interferon pathway with a previously unknown oncolytic virus. Nature medicine. 2000;6(7):821-825. doi:10.1038/77558

10. Melzer M, Lopez-Martinez A, Altomonte J. Oncolytic Vesicular Stomatitis Virus as a Viro-Immunotherapy: Defeating Cancer with a “Hammer” and “Anvil.” Biomedicines. 2017;5(4):8. doi:10.3390/biomedicines5010008

11. Connor JH, Naczki C, Koumenis C, Lyles DS. Replication and Cytopathic Effect of Oncolytic Vesicular Stomatitis Virus in Hypoxic Tumor Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Journal of Virology. 2004;78(17):8960-8970. doi:10.1128/jvi.78.17.8960-8970.2004

12. Dal Canto MC, Rabinowitz SG, Johnson TC. Status spongiousus resulting from intracerebral infection of mice with temperature-sensitive mutants of vesicular stomatitis virus. British Journal of Experimental Pathology. 1976;57(3):321-330. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/182197/

13. Plakhov IV, Arlund EE, Aoki C, Reiss CS. The Earliest Events in Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Infection of the Murine Olfactory Neuroepithelium and Entry of the Central Nervous System. Virology. 1995;209(1):257-262. doi:10.1006/viro.1995.1252

14. Shinozaki K, Ebert O, Suriawinata A, Thung SN, Woo SLC. Prophylactic Alpha Interferon Treatment Increases the Therapeutic Index of Oncolytic Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Virotherapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Immune-Competent Rats. Journal of Virology. 2005;79(21):13705-13713. doi:10.1128/jvi.79.21.13705-13713.2005

15. Schellekens H, Smiers-de Vreede E, de Reus A, Dijkema R. Antiviral activity of interferon in rats and the effect of immune suppression. The Journal of general virology. 1984;65 ( Pt 2):391-396. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-65-2-391

16. Johnson JE, Nasar F, Coleman JW, et al. Neurovirulence properties of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vectors in non-human primates. Virology. 2007;360(1):36-49. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.026

17. Gray Z, Tabarraei A, Moradi A, Kalani MR. M51R and Delta-M51 matrix protein of the vesicular stomatitis virus induce apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Molecular Biology Reports. 2019;46(3):3371-3379. doi:10.1007/s11033-019-04799-3

18. Day GL, Bryan ML, Northrup SA, Lyles DS, Westcott MM, Stewart JH. Immune Effects of M51R Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Treatment of Carcinomatosis From Colon Cancer. Journal of Surgical Research. 2020;245:127-135. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2019.07.032

19. Janelle V, Brassard F, Lapierre P, Lamarre A, Poliquin L. Mutations in the Glycoprotein of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Affect Cytopathogenicity: Potential for Oncolytic Virotherapy. Journal of Virology. 2011;85(13):6513-6520. doi:10.1128/jvi.02484-10

20. Roberts A, Kretzschmar E, Perkins AS, et al. Vaccination with a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus expressing an influenza virus hemagglutinin provides complete protection from influenza virus challenge. Journal of Virology. 1998;72(6):4704-4711. doi:10.1128/JVI.72.6.4704-4711.1998

21. Duntsch CD, Zhou Q, Jayakar HR, et al. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vectors as oncolytic agents in the treatment of high-grade gliomas in an organotypic brain tissue slice—glioma coculture model. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2004;100(6):1049-1059. doi:10.3171/jns.2004.100.6.1049

22. Tesfay MZ, Kirk AC, Hadac EM, et al. PEGylation of vesicular stomatitis virus extends virus persistence in blood circulation of passively immunized mice. Journal of Virology. 2013;87(7):3752-3759. doi:10.1128/JVI.02832-12

23. Muik A, Stubbert LJ, Jahedi RZ, et al. Re-engineering Vesicular Stomatitis Virus to Abrogate Neurotoxicity, Circumvent Humoral Immunity, and Enhance Oncolytic Potency. Cancer Research. 2014;74(13):3567-3578. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3306

24. Altomonte J, Wu L, Chen L, et al. Exponential enhancement of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus potency by vector-mediated suppression of inflammatory responses in vivo. Molecular Therapy: The Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2008;16(1):146-153. doi:10.1038/sj.mt.6300343

25. Wu L, Huang T, Meseck M, et al. rVSV(M Delta 51)-M3 is an effective and safe oncolytic virus for cancer therapy. Human Gene Therapy. 2008;19(6):635-647. doi:10.1089/hum.2007.163

26. Kannan K, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, et al. DNA microarrays identification of primary and secondary target genes regulated by p53. Oncogene. 2001;20(18):2225-2234. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204319

27. Yamamoto S, Suzuki S, Hoshino A, Akimoto M, Shimada T. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir-mediated killing of tumor cell induces tumor-specific cytotoxic T cells in mice. Cancer Gene Therapy. 1997;4(2):91-96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9080117/

28. Ebert O, Shinozaki K, Kournioti C, Park MS, García-Sastre A, Woo SLC. Syncytia induction enhances the oncolytic potential of vesicular stomatitis virus in virotherapy for cancer. Cancer Research. 2004;64(9):3265-3270. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3753

29. Obuchi M, Fernandez M, Barber GN. Development of Recombinant Vesicular Stomatitis Viruses That Exploit Defects in Host Defense To Augment Specific Oncolytic Activity. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(16):8843-8856. doi:10.1128/jvi.77.16.8843-8856.2003

30. Cockle JV, Rajani K, Zaidi S, et al. Combination viroimmunotherapy with checkpoint inhibition to treat glioma, based on location-specific tumor profiling. Neuro-Oncology. 2016;18(4):518-527. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nov173

31. Shen W, Patnaik MM, Ruiz A, Russell SJ, Peng KW. Immunovirotherapy with vesicular stomatitis virus and PD-L1 blockade enhances therapeutic outcome in murine acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(11):1449-1458. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-06-652503